Theona Morrison reports on the World Rural Health Conference in Limerick, Ireland

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) the definition of health is:

‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.

It is worth reflecting on those words. How often when we think about health, we visualise the GP surgery or something pertaining to the medical aspect of health care. And yet we probably instinctively recognise that our ‘health’ in the context of wellbeing is influenced by a whole range of factors, not least, our environment and the communities in which we live, work and socialise.

Approximately 600 health sector workers from across the globe attended the WONCA World Rural Health Conference held at Limerick University, Ireland in June 2022. CoDeL were the imposters! Why were we there?

The chair of the conference Dr Liam Glynn, Professor of General Practice at Limerick University and GP in a rural practice in the west of Ireland, was quoted as saying (see Liam’s blogpost here):

“The deep knowledge of individual and family health profiles that each of the community-based healthcare teams posses in relation to the population they serve and the therapeutic relationships on which these are based, are an enormous health asset in our healthcare system.”

In other words, there are a whole lot of influencing factors which impact health outcomes before we take a seat in the doctor’s surgery.

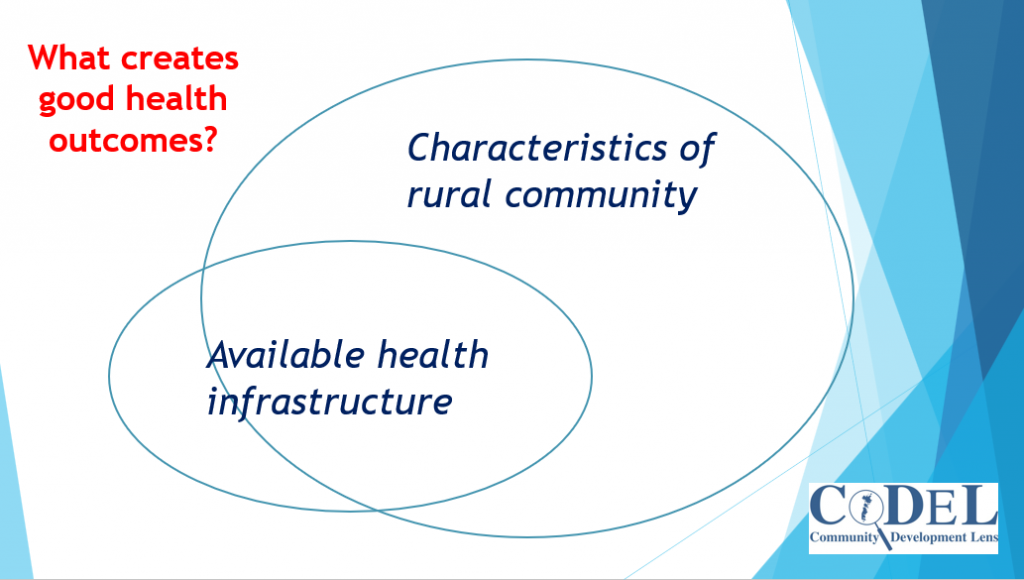

Liam’s words perhaps sum up well how health provision can work well when rooted in a community. We asked those gathered to consider what assets does the community have which contribute to wellbeing.

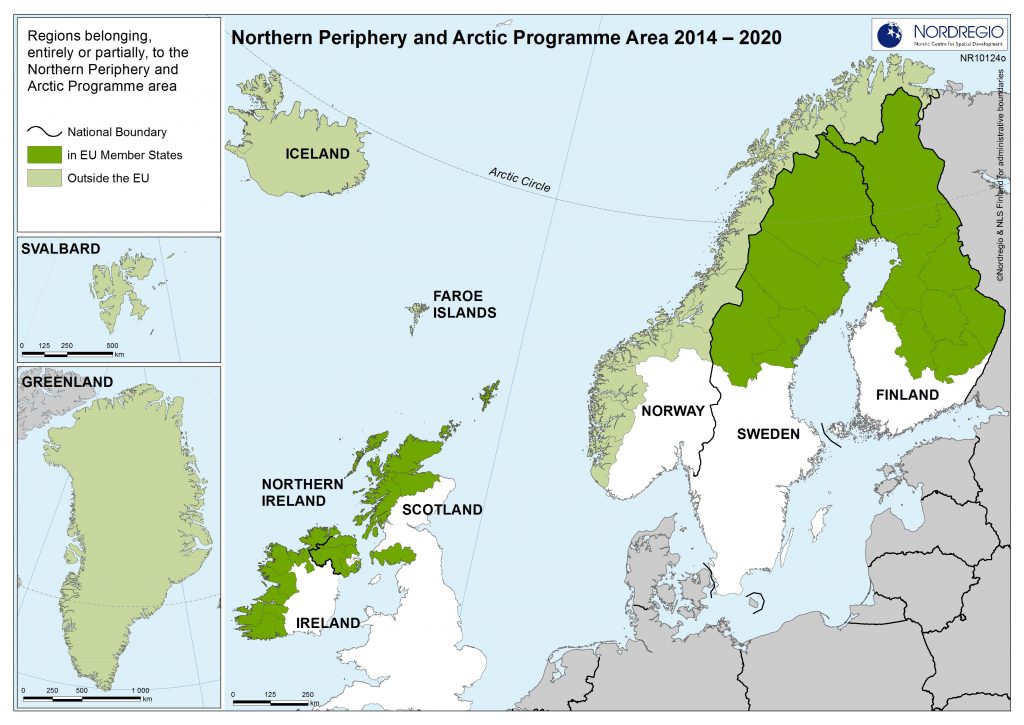

We found ourselves facilitating and delivering a workshop to an internationally diverse group of doctors and healthcare workers. We heard from those working with indigenous Sami communities in northern Norway bordering Russia; indigenous first nation communities in Canada and Australia; a township in South Africa; Ontario in Canada; Kenya, and much closer to home a GP working in the rural lands that straddle the Republic and North of Ireland.

When asked what positive actions they had been involved with or seen in the communities they were working, we were overwhelmingly moved by the examples of resilience and turn-around in fortunes that these communities had achieved.

Indigenous people, or at least communities which had historically been ruled by a n other, had often been perceived with a sense of powerlessness and valueless resulting in the well charted negative health outcomes that such communities suffered. This, combined with a global shift from rural to urban built on the narrative that rural often indigenous peoples needed assistance from those who ‘knew better’, has been applied across the globe against a backdrop of colonialism.

Yet, on the contrary, we heard story after story of remarkable resilience, in spite of being ‘remote’, socially and economically ‘deprived’. Something to do with what Liam had noted, ‘that deep knowledge of individual and family health profiles that each community healthcare team posses’

Strange isn’t it, that if we were to turn our attention to land, we know that according to the United Nations Environment Programme, ‘even though indigenous peoples make up just 6% of the global population, their lands shelter about 80% of the remaining biodiversity.’ This of course only includes those peoples who have indigenous status. There are those with linguistic and cultural inheritance unprotected by indigenous rites, but who also carry the knowledge of custodianship of each other and the land where they live.

We facilitated recognition of the assets communities often already have which contribute to the wellbeing of the people within those communities. We sought to present the context that health care infrastructure sits within the wider parameter of a ‘healthy community’ in its broadest but place-based sense.

Our findings have come to be framed under ‘Redefining Peripherality’, and increasingly as we present findings we also gather more lived-experience evidence across, health, economy and land. We see the paradigm really is shifting in recognition of what ‘rural’ provides for humanity.

Scotland’s Landscape Alliance (SLA) was set up in 2019 by a grouping of over 60 organisations with a common interest in raising awareness of the importance of Scotland’s landscapes to climate resilience and nature, economic performance and public health and wellbeing and, in doing this, gain public and political support for the better care of Scotland’s landscape and places to maximise future benefits.

A key message from SLA is that ‘Good landscape contributes to improved health and wellbeing, including in our poorest, most deprived areas and most vulnerable groups. The benefits of being in landscape are not limited to improvements associated with physical activity; using the outdoors improves mental wellbeing and encourages community cohesion.’

Bobby Macaulay has argued that community land ownership can contribute to better community health and wellbeing (see here).

So, I think we all instinctively know that being in what they call ‘good landscape’ is conducive to better wellbeing, if not exactly better health outcomes. After all, many of us take our ‘holidays’ in the rural beauty spots, indeed we know this only too well in places like the English Lake District, Snowdonia in Wales, the Scottish Highlands and Islands and the West ‘Wild Atlantic Way’ of Ireland. Places where in the summer time one can hardly move for the hoards of humanity that gravitate to such ‘hot spots’ to feel the benefit of ‘good landscape’.

The SLA goes on to say that ‘Greater numbers of people could benefit from landscape for health and wellbeing but cannot do so due to under-investment in design, implementation and stewardship of their local landscapes.’

What emerged from CoDeL’s NPA Covid-19 Response Project also confirms that rural holds many of the answers we will need.

“The picture that emerges from the extensive evidence of this project demonstrates peripheral communities have often shown remarkable resilience, drawing on many local assets and strengths, demonstrating significant flexibility and adaptation, generating much innovation and creativity (from technology to sustainable living) and many localised solutions. Often borne out of necessity, peripheral communities have tapped into their long history, rooted in generations of experience, of having to respond and adapt to changes and crises. They have turned what are often regarded as the challenges of peripherality to their advantage during Covid-19 as resilience factors ….”

“Peripheral areas demonstrated remarkable resilience during the pandemic and, on balance, performed relatively well during Covid-19, even though many did not have fully developed health infrastructure.”

Once again this reaffirms the impact of being in what have traditionally been considered peripheral locations, somehow ‘back in the day’, but just great for holidays. Somehow these places hold a great deal more than the tourist marketing would suggest.

Redefining Peripherality is not just in Scotland, Ireland, Nordic countries but stretches across the globe. It encompasses health, land (access, food production, ownership), also the social, environmental as well as financial economy and cultural cohesion.

We were the imposters at WONCA but collectively the narrative is changing and what we have shone a light on is not new, the resilience factors have been there for millennia, but they are gaining new recognition in the light of challenges such as Covid-19 and the climate emergency.