Part 3 of 3 for this week’s post

I recently watched a film with my children, Teen Spirit on BBC iPlayer, about East European immigrants on the Isle of Wight. It ends with a powerful song, including the words:

You love to tear me down

You pick me apart

Then build me up like I depend on you

In some ways this reflects a major strand of history experienced in places like the Outer Hebrides and the Highlands and Islands generally, “with the brutal suppression of Gaelic culture following the Jacobite rebellion, and then its apparent revival by outsiders”.

And like so many groups and peoples that have experienced oppression, this can become internalised. In our communities, many of us can be very good beggars, shouting about what we lack; and in the process even we sometimes forget our remarkable strengths and assets. At CoDeL we have experienced how political leaders have not wanted to share good news about positive developments and growth of our islands because it might undermine their ability to beg for more resources. Fortunately, renewed confidence and assertiveness is reemerging, not least among younger islanders.

Strong roots for such confidence can be found in our history. “Places seen in the past as peripheral were linked by sea to the rest of the world, known and unknown, and linked to Europe in fact more directly than most parts of Scotland. Here, on the west coast of Uist and on the doorstep of Tobha Mòr, was the self-evident highway of the oceans leading west and an ‘Atlantic corridor’ leading north and south.” (Hugh Cheape, The Road to Tobha Mòr).

Standing on the beach and facing the ocean, gulping down the sound and sight, my world rearranged itself. … Conceptual clichés of periphery and centre flipped over and slipped away. In a eurocentric and anglocentric culture, cities have been at the centre and islands at the edge. Moreover, this north-west edge of Europe seemed not to be familiar and any discourse from the past had inferred values of ‘otherness’, remoteness, strangeness or even backwardness. This was a landscape of condescension whose history was imposed and articulated from the centre.

Hugh Cheape, The Road to Tobha Mòr

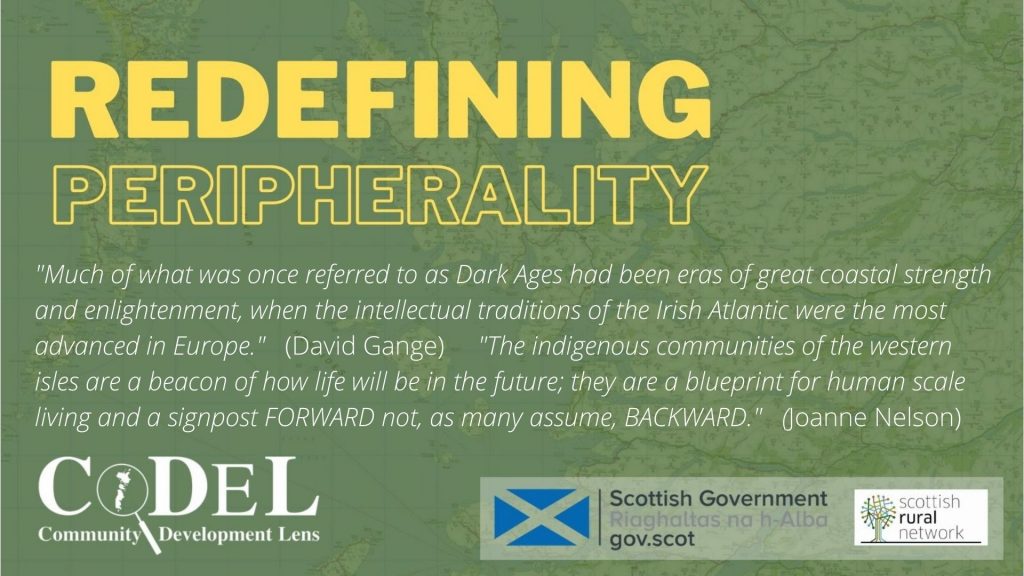

… such reversals abound. The so-called Enlightenment might be interpreted as the triumph of a few cities at the expense of other regions. In contrast, much of what was once referred to as Dark Ages had been eras of great coastal strength and enlightenment, when the intellectual traditions of the Irish Atlantic were the most advanced in Europe.

David Gange, The Frayed Atlantic Edge, HarperCollins, 2019

Hugh Cheape’s 2-part blogpost about Tobha Mòr in South Uist is beautifully written, and I would encourage you to read it. And I make no apologies for quoting sections of it in this blogpost.

“the Gaelic world of Scotland and Ireland had its own civilisation – and still has. More to the point for a modern audience, it has an autonomous history, generated in its own right and from within. … well before the European Renaissance, traditions of learning were as highly respected and as carefully nurtured on the edge of Europe as at its centre; and here on the edge was a major European language with a literature drawing in its origins on the oldest literary tradition in Europe beyond Latin and Greek. … Research has shown … that the traditions of learning fostered by the celtic church, which in turn made such a significant contribution to European learning, drew on and embraced pre-Christian and vernacular traditions in Gaelic to a unique degree.

“In modern re-assessments of Indo-European linguistics, the emphasis has moved from a European ‘heartland’ to the ‘Atlantic Celts’ and to a time-period reaching back before the first millennium BC. The study is of ‘continuity’ and ‘connectivity’, of migration and mobility, and this has tended to replace theories of waves of invaders and mass settlement. … The suggestion is made also that a ‘celtic’ language developed in Northern Iberia about 5000 years ago and that it was the lingua franca of the western sea-lanes.

“A vital aspect of this autonomous history for us today is that the Hebrides have been connected to a wider European culture and especially throughout prehistoric and early historic times. … Details can be teased out of Gaelic literature about Atlantic links with the Crusades and Islam, about trade and commercial life in Europe’s ‘12th century renaissance’ and continuing links with Spain which in turn linked into conduits of culture and learning from the Eastern Mediterranean. Ireland was a golden link in this chain and, with Spain, an intellectual source for other areas of learning such as philosophy and medicine, and material culture such as currency, precious metals and weaponry, textiles and wines.”

Is this all our own romanticism about a long-lost past? The simple answer is, no. With the pandemic, with the climate emergency, rural areas and islands are returning centre stage.

“The cohesiveness and the coordinated response that many rural communities developed organically, in response to the pandemic, really did mitigate a lot of harm of the pandemic. Despite being probably the greatest crisis in the lived memory of many communities, it did bring a new sense of confidence and possibilities to people living in rural areas.”

Liam Glynn, Professor of General Practice, Limerick University, Ireland

We want to build on (a) our inherited knowledge and intuitive understanding about land and sea, (b) a rich biodiversity thanks to low-impact lifestyles, crofting and protected habitats, and (c) extensive activity and expertise in local food production, recycling, energy generation and resource use.”

Social Enterprise Place Uist Brochure, p.12 (How many other places and communities could lay claim to such a rich and diverse asset base to respond to the climate emergency? )

The indigenous communities of the western isles are a beacon of how life will be in the future; they are a blueprint for human scale living, rooted in the landscape with a view to supporting the whole of the community, not just some. They are a signpost FORWARD not, as many assume, BACKWARD.

Joanne Nelson on Guth nan Siarach facebook, Feb 16, 2022

So we have a long and rich autonomous history to draw on, as well as so much remarkable contemporary good practice (see, for example, the Social Enterprise Place Uist brochure). What is critical for the survival of Gaelic as a vernacular language in the islands is that we reconnect with that autonomous history and build on our contemporary dynamism, drawing on all the myriad connections within and beyond our islands, as well as the growing confidence and assertiveness, that come from both past and present. Turning this into reality is not possible without significant decentalisation of decision-making power and resources to our islands.

In Norway, with its population of 5.5 million, there are 356 municipalities. In Scotland, with the same population size, we have 32 local authorities, including the vast Highland council, a third of the land area of Scotland and 20% larger than Wales. Combined with the three island authorities of the Outer Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland, it is larger than Belgium. It is deeply ironic that while many in Scotland want to be independent from control by a Westminster Government that is so distant and so different, Scotland itself continues to be one of the most highly centralised nations in Europe.

This lies at the heart of propositions for an ethnolinguistic assembly for Gàidheil or other decentalised governance structures, rather than the national structures currently in place that have failed to stem the decline in vernacular Gaelic. “The Urras model — with its central focus on Gaelic in this region and its particular needs – would ensure that community representatives were voted in and could wield influence across sectors in the region and indeed nationally. The alternative Misneachd model of smaller Gàidhealtachds (where Gàihhealtachd refers to people rather than place) is equally worthy of consideration.” (Guth nan Siarach).

The proposed Gàidheal assembly has the potential to create a protected space for the regeneration and recovery of an indigenous national group.

Iain MacKinnon, Recognising and Reconstituting Gàidheil Ethnicity

Let us make clear that we are not setting out some kind of exclusive agenda. Such an agenda would be far removed from the practice of our communities and the experience of islands. For those who may wish to see the film Teen Spirit where we started this blogpost, we would not want to transfer all the sentiments from the last song to our context, least of all the line “I wanted you to know that you don’t belong here”.

In the recent debates about Gaelic, Guth nan Siarach has argued strongly against the “distressing and offensive” suggestion of ethnically based prejudice: “Our members routinely put many hours, both paid and as volunteers, into sharing our mother tongue with as many learners globally and locally as we can”, and the same applies for communities across the Outer Hebrides.

As this week’s 3-part blogpost has shown, we have been part of a dense network of connections for millenia, and continue to be so. No community is free of prejudice, but, in contrast to some external perspectives, “the degree of isolation and remoteness that islands share have historically made them venues for encounters between different cultures.” This is very true even of the wee section of South Uist where I live. Close by is evidence of many Norse placenames, Irish and Ioanian monastic practice, a family that traces its ancestry to the Spanish Armada, the many links abroad, especially in Canada, created by the clearances, the ancestral home of one of Napoleon’s foremost generals, a castle that was built for the daughter of the (Scottish) Governor of Tangier (in Morocco), and the many merchant sailors in our community who have travelled the world (whose experiences are also reflected in local bardic poetry). When I first arrived here, I was at least the fifth person within the small Uist community that had extensive links with India.

If you ever want a good definition of ‘intersectional’, look at islands.

Rhoda Meek, Social Entrepreneur, Isle of Tiree

We are an open and welcoming community, as my family and I have experienced over the last 20 years, and we have benefitted from many immigrants, from within Scotland, Britain and further afield.

CoDeL is very fortunate to be playing a small part, in partnership with the Scottish Refugee Council and others, in supporting refugees in Scotland. In Scotland we rightly respect migrants from abroad as people and recognise their worth by referring to them as New Scots. In recent times the Outer Hebrides have welcomed and benefitted from immigrants from Pakistan and Syria (there is now even a mosque in Stornoway), and most recently from Afghanistan (thanks to the remarkable work, over more than a decade, of the Linda Norgrove Foundation based in the far west of Lewis), … from Eastern Europe and the Baltic States, and, in smaller numbers, from many other countries, such as Peru and Liberia. And it is striking how many from within these groups have learnt Gaelic.

As reported in the Stornway Gazette (26 April 2021) and The National (27 April 2021)

“A Syrian primary school pupil in Scotland has gone viral on social media after being commended for his progress in learning Gaelic. Abdullah Al Nakeeb, 10, moved to Stornoway from Homs four years ago. He had already picked up English as a second language but now, in Primary 6, he is well on his way to mastering a third language. Abdullah’s two younger brothers, Anas and Majd, are also learning Gaelic.

The Al Nakeeb family said: “We are really proud of Abdullah, he loves going to school here and Gaelic has become one of his favourite subjects. … since moving here he has managed to pick up Gaelic very quickly. … Hopefully Abdullah’s brothers will continue to follow in his footsteps, it would be great to have them all speaking a new language.”

And so migration and mobility continue to grow our web of connections and links within and far beyond our islands, triggering yet more encounters between different cultures, all the while deepening our commitment to “unlock layers of memory and meaning and reflect on who we are and where we come from” to develop and strengthen our complex Gaelic ethnic identity and the self-determination that is needed to achieve this.